Richard Benjamin has big plans to spread his love of poetry throughout the state. Though he’s a transplant from California (by way of New Jersey) Benjamin has called Rhode Island home for nearly 20 years. He now resides in Warwick with his wife, twin sons and daughter, and splits his time between teaching and volunteering his time.

Benjamin is a lecturer at the Rhode Island School of Design and at Brown University, where he lectures on Public Humanities & Environmental Studies. He’s also on the faculty of the MFA Program in Interdisciplinary Arts at Vermont’s Goddard College.

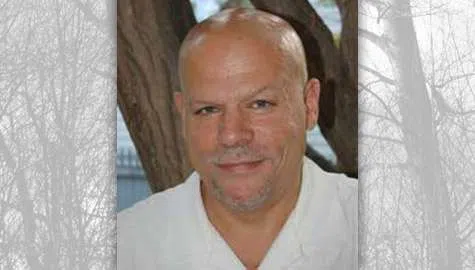

At 53, Benjamin said he didn’t expect to be Rhode Island’s newest Poet Laureate.

The position of State Poet is fairly new and was created by the legislature in 1989. Benjamin was nominated for the position in the fall, and got a phone call that he’d been selected. The process requires the nominees to put together a portfolio of sorts, putting their best work up for consideration alongside an outline of a plan for what they would do should they receive the Poet Laureate title.

A committee assembled by the Rhode Island State Council on the Arts chooses their favorite nominee, and the Governor appoints their selection. On January 9, Benjamin was officially appointed as Rhode Island’s fifth Poet Laureate. It’s a title he’ll hold onto for five years, and he hopes to do a lot of good with it.

Benjamin already devotes much of his free time to working in schools, assisted living facilities and community centers, but hopes to make statewide changes to the way people access poetry. He plans to create a statewide “Poets in Schools” program, something he already does on a smaller scale with his students from Brown and RISD. He’d also like to write a recurring column in the Providence Journal, as former Poet Laureate Thomas Chandler did, and would love to have a spot on a local radio network.

“I think there should be another way to have a number of listeners hear some things in poetry that they may not be aware of,” he said.

It’s also part of his plan to start a workshop series for teachers.

“They’re passionate about literature…but they rarely have any time to devote to their own practice,” he said of teachers. Benjamin hopes to create a way to nurture teachers’ artistic talents while letting them spread their creative wings.

And Benjamin knows how important teachers can be when it comes to fostering a love of language and literature: he talked of how his own teachers nurtured his love for the art form. His mother, a lover of language herself, introduced Benjamin to literature at a young age, but it wasn’t until middle school that Benjamin began writing himself. He recalled having a young teacher out in California that loved poetry; he had a crush on her and desperately wanted to make an impression. So he put pen to paper and gave it a shot.

At the time, Benjamin was in a class for “kids who were in remedial everything.” He remembered there were no windows in classroom, which was being used at the time as a dumping ground for the drama department’s props and costumes.

“It was a bizarre looking, almost-closet space,” he said. “It was rather demeaning as a place, but she was such an inspired teacher.”

So inspired, said Benjamin, his poetry began to morph into something great. Without his knowledge, Benjamin’s teacher submitted one of his poems for a student poetry contest, and it won. It was a victory for Benjamin as a writer, and as a hormonal seventh grader attempting to gain the attention and praise of his teacher.

For a student that had been, like his classmates, labeled as “recalcitrant” and “not worth teaching,” it was even more significant.

“Since we were the ones who weren’t supposed to achieve anything, it was kind of a remarkable moment,” he said.

The win in the poetry contest was the start of a lifelong career for Benjamin.

“I already knew I loved language and loved words, but I didn’t have a sense, up until that point, that I had any particular facility with it,” he said. “I found that it could be a point of discovery for me in my own life, and possibly move other people and be important to them as well.”

Today, Benjamin’s words have been printed, praised and anthologized. He also has two of his own books: “Passing Love” and a new book coming in March called “Floating World.”

But a lot of his work, he said, will never make it to the pages of a book. Drawing inspiration from nearly everything, Benjamin said many of his poems are “snapshots” of life around him. He spent a lot of time writing about his children when they were young, and most of those poems, to him, are more like photos for a family album.

And family serves as source of some of his most intimate poetry, like a poem called “Delivery” that he dedicated to his twin brother, Reed.

Delivery

(for Reed)

Twins give birth to each other

in ways only their parents

can conceive: wear the same

clothes, be individuals, each

other’s best friends, make

friends with different

people: the contradictions

we saw in the other’s eyes.

Once, when our mother

told us to sit still

in her garden until

she came back,

ants crawled over

both of our bodies

indiscriminately, sparing

neither one of us. Staring

at you, witnessing my stings

in your eyes, I do not remember

which of us

cried first.

“Anything in your mind is worth writing about,” he said. “It could be the merest and slightest thing in your life.”

That’s something Benjamin tries to remind his students, especially the high schoolers he works with when visiting schools.

“There’s this idea around poetry that… ‘I don’t know what to write about,’” he said.

Benjamin said those looking to try their hand at poetry shouldn’t worry about finding a subject that others have deemed “important.

“You’re not pulling poems out of the thin air, because the air is thick with poetry,” he said. “You can’t help yourself. The most obvious or banal starting point can lead you somewhere important.”

For his own poetry, “I tend to be fairly unfiltered,” he said.

Recently, Benjamin pulled inspiration from two articles he read. One was about a 95-yeard-old cellist who played a reproduction of his beloved cello – the original had been sold by his children – at his own birthday party. Benjamin remembered that the cellist’s daughter said her father “didn’t know the difference;” Benjamin refused to believe that.

The other article was about octopi; the way they build stone shelters around themselves, how their intelligence lies in their arms and how their eyes are similar in construction to humans’.

The two stories, though starkly different, kept clashing in his mind. This was the result:

The Octopus knew how to get what it wanted

Like you, an octopus

has some idea

of what it needs

before it feels safe

enough to sleep.

For me at five: leaving

a light on, covers

pulled tight, back

up against the wall

as if blocking all

but one approach might

make a difference. An

octopus places rocks

in front of its den

before it goes

to sleep, small

stay against

threats.

________

I once heard

a cellist say

that, at 95,

he could still

play each note

he heard in

his head.

He was

dead in

less than

a year, &

later, after that,

his own daughter

said during his last

birthday party he hadn’t even

realized the instrument he’d been

playing was a replica, not one he’d loved

like a partner for sixty years, wanted to

to sleep with near the end, not

one Antonio Stradivari made in

1707, Forma B, one of 20 left

in the world in 2012. She said

it was sad he had come to a point

in his life when he could not hear

the difference.

________

You are wondering

what this has to do with

the boy or the octopus

or anyone else who needs

to feel safe before she goes

to bed.

In his ears

he knew

he’d lost

the voice

he’d come to love more

than his wife’s, but,

always one to rise to the

occasion, held his mind

against that knowledge

like a locked door in order

to play, for them, one

more time, before going

off to sleep trusting

they would hear

between notes, even these

inferior ones, what he had,

at last, to say.

_________

An Octopus’s eyes

are most like a human’s

though it carries its

intelligence, mostly,

in its arms.

It is not accurate

to say that, for humans,

it is only in the head, hearts

being what they are.

___________

Strings want finger-

tips to find them,

a body to be wrapped

in someone’s arms,

even if only two, &

this is the sound of

three rocks making

safe a silence.

For Benjamin, earning the title of Poet Laureate means having a new platform on which to spread his love of the written word.

“There isn’t any poetry that I don’t love,” he said.

Whether 19th century poetry or contemporary hip-hop, Benjamin said he can find poems in any genre that he enjoys. He mentioned Lucille Clifton, Adrienne Rich, Robert Hass, Mark Doty, Kevin Young, U.S. Poet Laureate Natasha Tretheway, Shin Yu Pai, Alberto Rios and Li-Yong Lee as several of his favorite poets.

Though he has lost count of the number of poems he has written himself, Benjamin rarely recites his own work, and turns instead to his colleague’s poems when giving a reading.

“Although, a 13-year-old last year told me that he really thought I should [recite my own poems], and so I’m thinking about it,” he said with a smile. “I’m thinking about it.”

Kim Kalunian

Kim Kalunian

An award-winning journalist and theater critic – and a performer at heart. Kim’s talents have taken her from the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade in NY, to stages in Boston and Providence’s own Trinity Repertory.![]()

![]()

![]()